Ómós Digest #33: Boiling Point in the Kitchen.

A raw and brutal reflection of the restaurant industry.

It's been five days since I watched Philip Barantini's film Boiling Point and I still find myself lying in bed staring into the darkness, reeling from its rawness and intensity.

The movie throws you deep into the world of a professional kitchen. It ignores the typical glamour depicted by generic food films (like the Netflix docuseries Chef’s Table), where the emphasis is typically placed on the nobility of the chef. These types of shows tend to depict the romantic rise of a chef and present them as demigods, rather than the 99.999999999% of what it actually takes to run a successful restaurant. Instead, Boiling Point focuses on the latter, highlighting the dark and untold reality of life in far too many restaurants around the world. I know this because I’ve worked in many of them.

Before we get into it, I want to make it clear that this is not a film review. There are far more accomplished writers (I’m not a writer, I’m a chef who writes) to critique a film, so let’s leave that to the professionals. What has compelled me to dedicate this week’s newsletter to this film is— yes, Boiling Point is of course a film set in a restaurant, and yes, this newsletter encapsulates many aspects surrounding food, but the primary reason is that the film tells a message. Boiling Point unearths the impact that imbalance and life’s pressures can have on the human body, how stress can amount to destruction and how that transpires to affect a whole restaurant's ecosystem. The film reels you into the truth-telling grind and reality of life in a bustling restaurant, revealing the countless scenarios and life experiences I have witnessed firsthand. We experience the many moving parts and unexpected problems each day brings forth, leaving you floundering in disbelief. The film perfectly demonstrates what goes on behind the scenes in restaurants. That is, once the Netflix cameras go home.

I was not alone at the time of watching. I was accompanied by my girlfriend’s parents in their home in Missouri, where we were visiting for the holidays. Truth be told, as we sat down I was nervous. Having seen the trailer, I was prepared for a heavy-hitting hour and a half flashback of my past. I had pre-warned them that this was heavy stuff. The opening couple of minutes did not disappoint. Immediate tension is experienced in the kitchen, brought on by a safety inspector - every kitchen's worst nightmare. It should be noted that no matter how attentive your kitchen might be, no matter how regimental you are with your paperwork, or how disciplined you are with your clean down, when it comes to food hygiene, in every team there is a weakness, and believe you me, the health inspector will be the first one to locate it.

I recall the time a hygiene inspector came to Geranium in Copenhagen. We had just won 3 Michelin stars and rose to 18th on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants List. Our bookings had gone through the roof. Quiet lunches were now bustling and big names were finding their way into an already full restaurant. What initial celebrations were had were quickly forgotten and replaced by tension and high levels of stress. We were doing our very best to cope, barely above water, in dire need of additional storage, more cooks and a day off. Of course, an unexpected visit from the health and safety officer had the entire team scrambling. Head Chef Rasmus Kofoed, who owns Geranium with Søren Ledet were both sweating at the guilds; a scene captured pristinely in Boiling Point when the inspector parades around the kitchen, questioning junior members of staff who were prepping ingredients in an area they perhaps should not be. These are common occurrences in many kitchens.

Nevertheless, a couple of weeks following the inspector’s visit, we had our response. Geranium had been reduced from 5 stars to 3 for health and hygiene. We were in total shame. A dark shadow loomed over us despite our recent success. In Denmark, such a notice must be visible at the restaurant’s entrance. The media were on it in a flash. It turned out the fish fridge had been too high in temperature, a result of continually opening and closing the door. It meant that when probed, the fish read a temperature deemed unsafe, which is enough to put shame on the restaurant and its staff. In Boiling Point, following the health inspector’s exit, the debilitated Stephen Graham unleashes his wrath, cursing blindly and demonstrating the macho bravado seen all too often in the kitchen.

Reeling you in

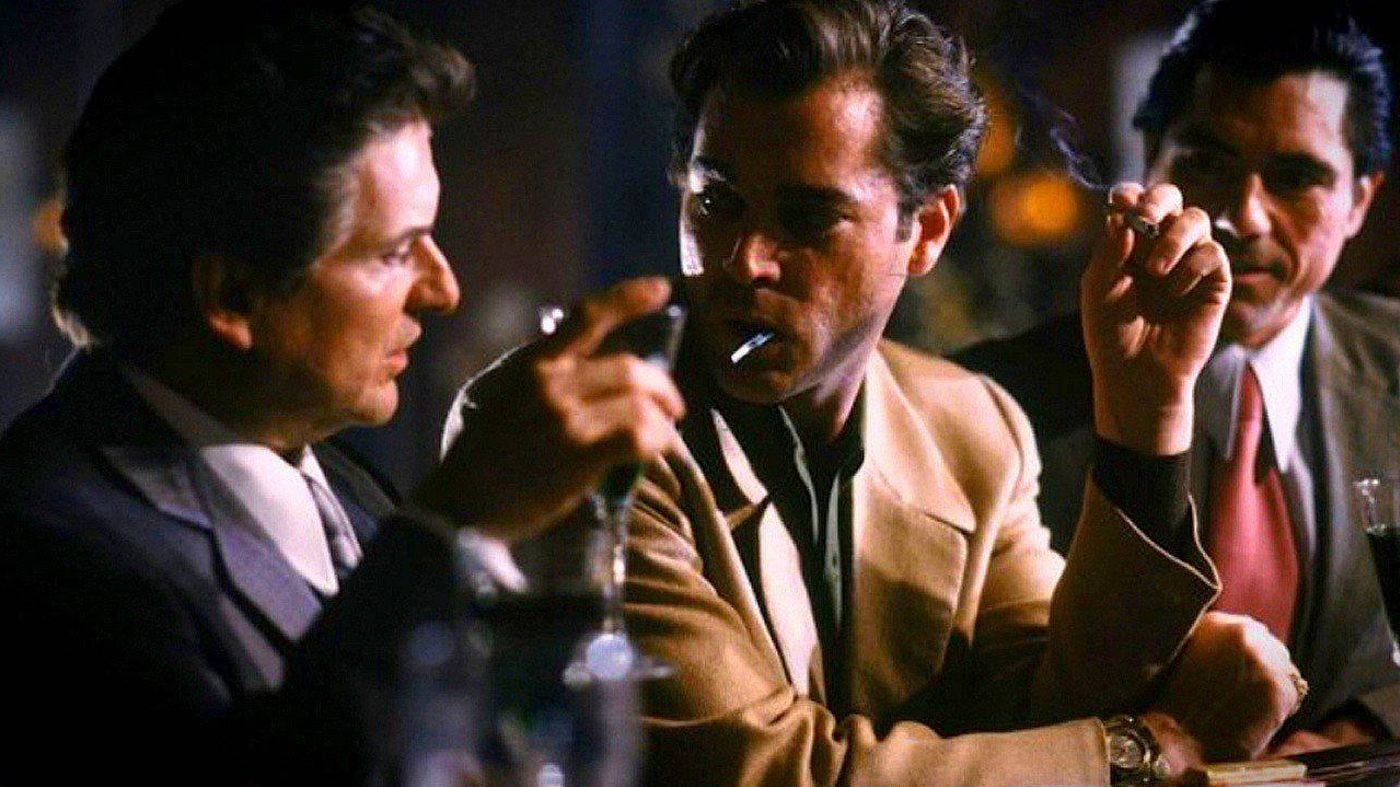

Interestingly, Boiling Point is filmed in one take, otherwise known as a ‘oner’ which is a long, continuous shot taken by a single camera known as a Steadicam (I know this part sounds a bit like a review, but I thought it was important). The technique was first implemented in a scene from the cult classic Goodfellas, a famous cinematic scene that sees us follow Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) to the Copacabana nightclub. The camera twists and turns down narrow corridors of the club, through the back of the house, walking us directly into a bustling kitchen (maybe this is where Barantini got the idea) all the while Hill hands out tips to staff members at freewill. The Steadicam, I’m told by my friend and actor Ross Gaynor, is a chest-rigged mechanism developed to keep a camera ‘steady’ - thanks Ross. In Boiling Point, this method of filming takes the audience on a journey, transporting us as if we were a part of the scene. Interchangeably, the Steadicam allows us to follow the various relationships and dynamics present in the restaurant at Jones & Sons. We experience the intense and stern interactions between chefs and waiters on the pass. The fear, confusion and reluctance to communicate. How the chefs bark at the waiters, ignorant to what might be happening in the dining room, oblivious to the nonsense that resurfaces each night!

With all this detail, I wondered how much time must have been spent teaching the actors to imitate a cook's technique and movement. I did a little digging to decipher which chef had helped with the curation of the film. I found that not only were a host of America’s best chefs brought in to teach the actors, the director Barantini was a head chef in a previous life. Not only that, they filmed it in Jones & Sons, the actual restaurant in Dalston where Barantini used to work!

Initially, I was unsure what impression the film had made on Eva’s parents. Had they fully been able to appreciate the details only a chef might see? Had they picked up on the kitchen slang or the casual romantic exchanges between bar-staff? Then there’s the nonchalant attitudes of the part-timers, the inappropriate joking and mockery all too common in the kitchen. Each scene is in fact awash with references I’ve experienced in restaurants. In my earliest days in a dark dingy restaurant, I recall the nurturing role of a female pastry chef working in the back, where the bright neon lighting shone a subnatural glare where guests couldn’t see. I’ve had the privilege of cooking for some of the world’s best chefs, many of whom clasp their hands in prayer as an expression of gratitude for their meal, as if we had just performed some culinary miracle - the messiahs of the culinary world. Although I’ve never mentioned it to anyone before, I’ve always wondered why they do that? To my surprise, Barantini had also picked up on it and it was perfectly executed by the sneering celebrity chef (Jason Flemyng) dining that evening, much to the annoyance of aggravated chef Andy.

The following day I could sense that the film was on Teresa’s mind (Eva’s mother). It did not matter that such intricacies had gone unnoticed. They left a mark on her nonetheless. Together we replayed the scenes, over and over, she recounted her disbelief towards the emotional rollercoaster she had been brought on through the lives of the characters. How on earth could people possibly work in such anxiety-inducing conditions? Day in day out, having to relive that pressure. How could diners be so horrible to staff? How were the chefs so terrifyingly unapproachable? How and why do staff put up with such behaviour? While the flaws certainly outweigh the positives, it was obvious she could see the good through the bad. She noticed the pace of service, appreciated the synchronisation of the kitchen and the overall team effort to produce the seemingly impossible. For the split second when everything was running smoothly, when everything aligned amounting to an ambrosial blur, the perfect symphony of service captured Teresa's imagination.

Hell’s kitchen

When asked why kitchens are so stressful, I am often reminded of a conversation I had with a surgeon. We compared scenarios of a busy restaurant service and an operating theatre. While cooking a piece of fish may not seem like a life or death scenario, or of the same importance as surgery, these are two professions where immediacy and precision are of key importance. Two environments where abuse of power is omnipresent. Chefs take food very seriously, often to the point of extreme. For individuals whose main focus is to ensure a guest’s happiness, there’s a lot on the line, including one’s ego. Seconds make the difference, a couple of inches or an angle askew can result in disaster, throwing a whole service in jeopardy and amounting to high levels of stress. One can certainly draw parallels to the operating theatre here.

What is evident in Boiling Point, and so often the case, is that these characters are sad individuals who resort to drugs, violence and abuse as a result of this stress and inner vulnerability. It’s undeniable that many kitchens are broken. Despite this, ever since I got the first taste of a professional kitchen, cooking has become the focus of my existence. Boyhood dreams die hard and good sense be damned, to open a restaurant became and has always remained a burning ambition. That being the case, it’s up to us, this generation, to change the mentality that a kitchen is a brutal environment. The Independent’s Katy McGuinness recently spoke to Irish chef Max Rocha in an article you ought to read. Discussing how kitchens are tough places, Max is determined to change the culture and avoid the traditional pitfalls of hospitality, noting that, “if the staff are happy then the food will be happy”.

Restaurants possess a certain degree of euphoria that will always attract a certain individual. The industry has forever been a magnet for kooks, wanderers and those in search of an adventure. Let’s just cut the bullshit, get rid of the bravado, and instil good working conditions. Then there’s nowhere more I’d want to be.

Boiling Point is now available in cinemas and Amazon Prime. Please watch it. And come back and share your thoughts!

Really interesting reflection ….and I particularly like the call “it’s up to us to change the mentality that a kitchen is a brutal environment “…. We believe that this must also be part of culinary education, which is very much the ethos of ‘The mindful kitchen module-health & wellbeing for chefs’, at TU Dublin(Tallaght Campus). Educating chef students in positive kitchen culture and their own well-being is an investment in future kitchen leaders.

I was interested to read about your interest in the parallels between the kitchen and the operating room. I've previously been worked in kitchens - including as an assistant development chef at The Fat Duck - and am now a surgical trainee. The historical issues of abuse and megalomania exist in both spheres, and both chefs and surgeons face similar levels of pressure at the upper echelons. There is a lot that could be brought from the kitchen into the operating room, and vice-versa. You may be surprised at how relaxed operating rooms feel compared to a professional kitchen, though there is certainly a move towards quieter kitchens these days. It's something I'm fascinated-by and will hopefully be doing some work in to investigate what we could learn from each other. Food for thought...