Hello,

The Ómós Digest is a reader-supported publication, of which all contributors are paid. Please consider supporting this continued writing and research and helping to expand our amazing team by upgrading to a paid subscription for €5 a month or €50 a year. This newsletter brings you on that journey about the food you were looking for or perhaps never knew existed. It is our quest to expand on what we don’t know and to share with those who care.

A couple of months ago I ate at the acclaimed Estela restaurant in New York, run by the city's hottest chef right now, Ignacio Mattos. I shared a table with the head chef of Mirazur and the sous chef of The French Laundry; two restaurants I have followed since their birth. Somewhere between mouthfuls of endive (if you have been to Estela then you will know), we got onto the subject of knives. JC (of Mirazur) announced that he had properly learnt to sharpen his knife through the video I created on Instagram during covid. I was absolutely humbled, but more so shocked. I was in awe of these guys and their respective restaurants. It just goes to show that we are constantly learning. It was that moment that sparked the idea to write this newsletter. I hope it is of value to you and serves you well.

That’s sharp, chef.

If you are reading this, there’s a high probability you were gifted a knife this Christmas. No? Perhaps it is the blunt knife you acquired last year then, surely forged by a scraggy-haired, barefoot bladesmith located somewhere on the west coast of Ireland. Despite being aesthetically marvellous (its preserved horn handle no doubt sourced from the boglands of Co.Clare), the knife's edge no longer cuts through a mushroom. Rather ashamedly, as dinner time approaches, the kids are screaming, the dogs barking and when push comes to shove and notions be damned, you find yourself sooner reaching for the €9 IKEA VÖRDA knife over the blunt carbon artwork affixed on the wall before you.

There are a few reasons why Irish knives have become one of the most sought after gifts at Christmas. 1. The pandemic got us back into the kitchen and subsequently, we realised our kitchen and equipment required immediate updating. 2. We now value process and craft over materiality. The urgent requirement to think sustainably has caused us to want fewer things and refocus on better quality things. 3. Irish pride is at an all-time high as we gather the courage to carve a path of our own. A knife is a tangible method of connecting with our ancestral roots and traditions. After all, is there anything that induces our primal needs more than the gift of a blade? 4. There are at least three (maybe more) expert knife makers in Ireland, producing blades of the highest quality. And so, as we swap iPhone for mammoth tusk and 14 carat gold for 16 layers of Damascus, nothing eclipses the primaeval sensation of drawing a blade from a hand-crafted saya on Christmas morning…

Consequently, Irish bladesmiths are seemingly in high demand. If you have managed to get your hands on an Irish-made knife this year, you deserve to be congratulated. Either you are remarkably patient, have something of bartering value or have connections on the inside (all of which are valuable assets in themselves). However, if you do find yourself firmly rooted at the bottom of a knife list, with your chives requiring immediate assistance, then allow me to suggest to you this 210mm Gyuto knife by Japanese bladesmith, Takamura. It’s one of the best value for money knives I have. The blade is thin, which makes for easy sharpening and it’s aesthetically elegant.

Just like making sourdough, knife sharpening is an eternal skill. It's a process that improves with practice and unlike sourdough, it won't die in your fridge. Now, let’s get to work.

Sharpening explained

Out of the box, regardless of its quality, almost every knife is sharp. However without proper care and maintenance, whether you spend €10 or €500, after a matter of weeks of continuous use, the knife will dull. What differentiates knives from good to bad or high to low, is the quality of craftsmanship (most significantly, quality metals and the forging of metals). This of course dictates the knife's ability to hold an edge. Without learning to properly sharpen your knife, spending big is simply not worth it. To be honest, I have ruined many knives over the years, mainly because I hadn’t learned how to take proper care of them.

Stones VS honing steels

When you cut and slice food, the edge (or bevel) of the knife begins to dull. Not only that, it actually begins to bend and microscopically curl, causing the knife to become entirely dull. This bend is called a burr. The purpose of a sharpening stone is to remove that burr by removing a layer of the metal and subsequently realigning the edge.

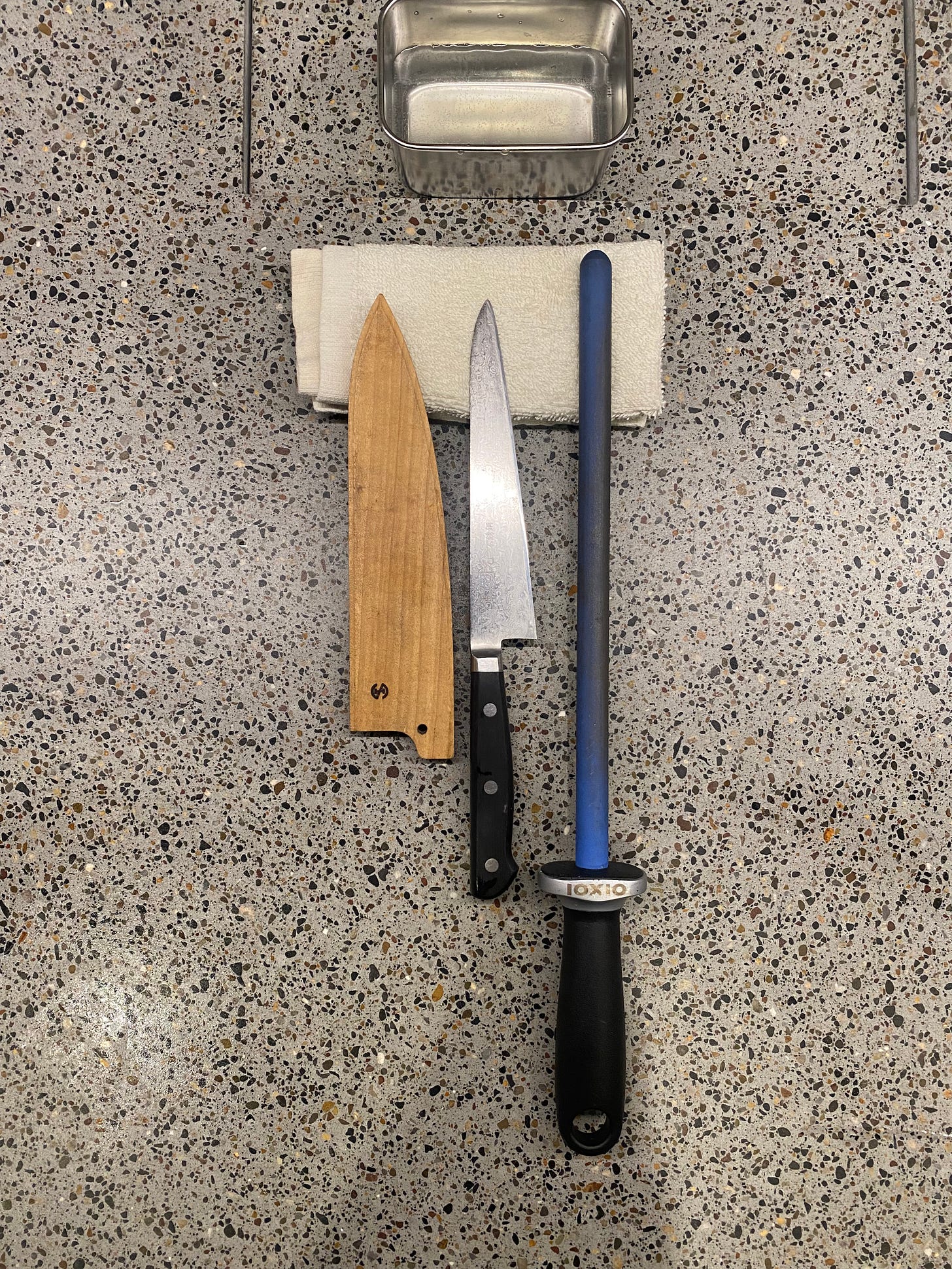

A honing steel works differently. Although most home cooks refer to a honing steel as a ‘sharpening steel’, the honing steel is not designed to sharpen at all. Its purpose is to realign the bevel (knife's edge) as it begins to bend left or right (which will naturally sharpen the knife temporarily). If the knife's edge is allowed to bend and roll over, the honing steel becomes entirely useless and your knife is in need of a stone.

After a knife has been realigned with a stone, the edge can be maintained through application of the honing steel temporarily, or until the knife requires a fresh application on the stone.

Types of stones

Medium grit (1000- grit): the most used grit for knives and best for removing small burrs.

Low grit (5000+ grit): these stones are for finishing your knives following the 1000 grit. They will refine your blade, making the knife sharp for longer.

Very low grit: (200 grit): low grit stones like these are for damaged blades that require a full removal of metal. They should be used with caution and only when the knife is in bad condition and requires a new edge (chips).

Advice for beginners

Knife sharpening is a bit of a knack and takes a bit of practice to get used to but after a while, it will feel like second nature. There are several steps to sharpening, taking into account the ratio, followed by finishing and stropping. Despite inevitable impatience, my advice is that you start with a cheaper knife to learn on. There’s a high probability you will not get the angles right to begin with.

How to sharpen your knife using a stone: (step by step).

Begin by soaking your stones in cold water for at least 20 minutes (overnight is perfect but not necessary).

On your workbench, set your soaked stones on a folded damp cloth or on a sharpening base if you have one.

Have a small container of cold water next to you. This job is a little messy so perhaps wear an apron.

Wet the stone a little with water (1 tsp worth is fine).