Welcome to the Ómós Digest. This newsletter will hopefully bring you on that journey about the food you were looking for, or perhaps never knew existed. It is our quest to expand on what we don’t know and to share with those who care. If you haven’t read Newsletter #1 yet, it can be found here.

Give a gift:

Consider gifting a subscription to someone you feel may will enjoy the Ómós Digest!

Furoshiki

Origami has always fascinated me. It's a recreational activity that spans over a 1000 years, with origins in Japan and China. With the application of a few considered folds, a flat piece of paper is transformed into whatever shape your imagination desires. While it’s not the most elaborate of folds, the shape I was most taken with as a child was the origami drinking cup. The fact that a flat sheet of paper could be shaped into a vessel that could be filled with water fascinated me. Today, this interest continues, as I find ways of making plates, bowls or vessels from raw materials. On the eve of my first ever pop up circa 2012, lacking the funds for handmade ceramics, I recall shaping folder dividers into vessels capable of holding 63° sous vide egg yolks, back when writing the temperature of ingredients on menus was cool.

This discipline of using natural and sustainable materials is practised all over the world.

In India, local sal leaves, almost circular in shape, are placed over one another, woven then folded into a cup similar to my 10-year-old origami cup, albeit more charming. Similarly, layers of these interwoven sal leaves succumb to great pressure to produce a wonderfully unique plate that is as beautiful as it is environmentally friendly. You can find it here. In Ireland, the Skib is a basket made from woven willow that acts as a strainer for cooked potatoes. It has been around for centuries but it was Joe Hogan, in his book Basketmaking in Ireland, that brought the Irish potato basket back into everyday use. Joe did a lot of research into traditional Irish baskets. One of them is the skib. Skibs were often quite large, one of the reasons being that many dwellings at the time didn’t have a dining table due to sheer poverty. The basket was placed on top of the cooking pot which acted as a table for the family to sit around. The potatoes were often dipped in warm buttermilk, a byproduct of butter production. Out of necessity and ingenuity, practical uses for commonly found local materials were found. Many of which remain ingrained in our cultures today, thanks to the continued work of skilled craftspeople.

My mother Róisín de Buitléar, is one of Ireland’s leading artists and glass blowers. She is a great inspiration to me and it is wonderful that our disciplines often crossover. We share stories and insights into the people we meet along our journeys. One of these craftspeople to whom my mother introduced me to is the extraordinary basket weaver Hanna Van Aelst. Originally from Belgium, Hanna has been based in Tipperary for over 20 years. Her work spans across functional and sculptural work, including skibs of all sizes, traveling baskets, and the most beautiful feature pieces. There is a wonderfully philosophical approach to her work, marked by her gentle character, the eloquent manner in which she expresses her work, and deep connectivity with nature. Hanna is currently designing bread baskets for me, along with oshibori hand towel baskets.

The art of tradition

Oshibori towels are rooted in Japanese hospitality culture. Served cold in the warmer months and hot in the colder months, they are a palpable means of pausing and refreshing prior to or during a dining experience. In fact, Japan has a long tradition of puppeteering and yes, as I write this, I acknowledge that we are now entering a deep rabbit hole. In the last 70 years, a new form of puppet has appeared, made from chopsticks and oshibori (here we go). The towels are not only used to clean hands but to entertain the businessmen and women of the vast cities of Japan, where going out for dinner and drinks is a common activity in Japanese business culture.

In this video, the puppet’s dance moves are based on traditional Japanese choreography. One of the hallmarks of Japanese dance is to pause. Just like when a great storyteller pauses between lines, the Japanese dancer freezes for several moments before continuing, bringing the oshibori towel a sense of life. The practice became so well appreciated as a form of business entertainment that there are now classes to teach the movements to company managers.

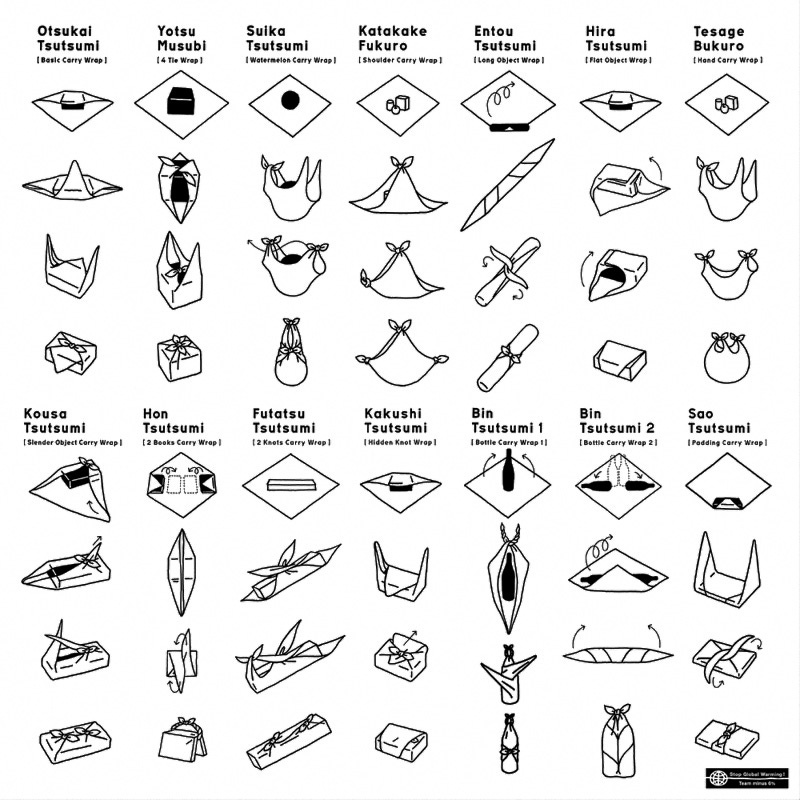

One of my favourite examples of practical art forms is the furoshiki wrapping cloth. I was very lucky to work with many inspirational chefs at Noma and one of those was Japanese chef Jun Takahashi. Noma’s food has always placed its focus on identity, creating new forms of cooking and flavours that are geographically unique to Denmark. Jun once told me: “While we can be inspired by other countries' food and culture, for example Japan, it’s important that our food does not taste Japanese”. This frame of mind applies not only to food, but also to objects and practices, such as the Japanese gift cloth wrapping tradition, known as furoshiki.

Knot your average wrap

Furoshiki garments are traditional cloths used to wrap and transport objects. My mother introduced me to furoshiki, having spent a year working in Japan as a student (she worked in a haricots bean canning factory). Although canned beans are no longer high on her agenda, she was inspired by the many practical art forms implemented in Japan. For years, rather than receiving gifts wrapped in paper, our Christmas mornings commenced with unwrapping beautiful furoshiki cloth, a far more personal and sustainable form of gift wrapping.

Furoshiki cloths are typically square and made from cotton, linen or (for the most prestigious moments) silk. It is such a useful method of wrapping gifts, protecting products on journeys and with that, also saving the environment.

The name furoshiki was applied during the Muromachi period. Furo means ‘bath’ and shiki means ‘spread’. It is believed that a Shogun (a military ruler) during this era, installed a large bathhouse in his residence and invited feudal lords to stay and use the facility. These guests would wrap their kimonos in furoshiki cloth while they bathed at the sento, so as to not confuse them with others. Often, the cloths were adorned with family crests and emblems as further indications of who they belonged to. Many stood on the fabrics while drying after bathing, hence the translation of the word to ‘bath spread’. As the practice became more widespread, it wasn’t long before the custom spread to other avenues such as wrapping books, gifts, and merchandise. In 2006, in an effort to increase environmental awareness and reduce single-use plastic, Yuriko Koike, Minister of the Environment, promoted furoshiki cloth. It is during this period that the spread and contemporary practices accelerated in use. Today, it is commonly used by Japanese schoolchildren to carry bento boxes and by gift-givers around the world as an environmentally friendly way of gift wrapping.

What I personally love about furoshiki is the act of returning the cloth to its owner. While you can pass the furoshiki on and present it as a gift to the desired recipient, the cloth can be returned to its owner upon receipt of the gift. Others keep the furoshiki cloths within gifting circles, so that one day it returns to its owner. Over the past year, my friend Peter and I, who is also a chef, occasionally gift each other small jars of preserves. The contents of course vary, but the actual jar itself is always the original one, passed back and forth. Our tradition always feels extremely personal and thoughtful. Yesterday, having met up for a coffee with Peter, he presented me with a jar of 2 year old homemade Guinness miso (which doesn’t taste Japanese). Less venerable though, was the compostable plastic that the jar was presented in. The plastic bag did a complete injustice to both the delicious miso and what the gift represented. Now, what if a furoshiki cloth delicately covered that jar?

Envision the French using furoshiki in their bakeries, replacing the classic twist of paper that so characteristically wraps baguettes, with a beautiful cloth that was returned the following morning. If wine shops wrapped each bottle in an industriously transportable tie, or if iconic Lakrids in Denmark enveloped their packets of liquorice in beautiful Danish linen. Pierre Hermé’s prestigious macaron boxes could even be heightened by a silk cloth wrap. The possibilities for furoshiki are endless. Observing our own culture can give us the awareness to acknowledge and unlock the potential that may otherwise be missed or underappreciated. Taking pride in what we possess can give us a greater sense of identity, to more honestly explore what exists elsewhere, and align them with our own traditions.

Next week we are very excited to launch a new product; Our Foragers Tool Pack. The pack will include a number of beautiful Japanese tools to aid you or your loved ones with all of your foraging needs, all wrapped in our Irish-made furoshiki. More to follow next week.

As always, thank you for reading the Ómós Digest. This is newsletter #20, so if you missed our previous editions, you’ve got plenty to catch up on, including our Something Saucy offering. You can also check out omos.co if you’re curious about our story.