Ómós Digest #93: The Menu.

By Cissy Difford.

Hello!

Thanks for joining us! The Ómós Digest is a reader-supported publication, of which all contributors are paid. Please consider supporting this continued writing, research, and expanding our amazing team by upgrading to a paid subscription for €5 a month or €50 a year. This newsletter brings you on that journey about the food you were looking for, or perhaps never knew existed. It is our quest to expand on what we don’t know and to share with those who care.

Are you the kind of person that reads the restaurant menu online and mentally signs off on what you’re going to eat before you’ve even stepped foot in the restaurant? Or do you arrive hopeful and unswayed in your decision because you want to keep an element of surprise to your dining experience? Whichever side you fall on, we can all agree that the menu plays a huge role in our restaurant experience. They are scrawled in handwriting on chalkboards, printed on thick gsm paper, laminated in a display book or accessed via a QR code. These little things you see at the beginning of your meal might seem insignificant but are one of the first impressions you get of your chosen restaurant. Not only this but they are historical documents that tell us so much about that period of time. For me, menus are also references that inform my work. I’ll often browse my favourite places online and see what they are offering as a way to seek inspiration and stay up to date on trends. However, the way menus are written these days leaves a lot to the imagination (perhaps too much). I’m talking about the short, 2 or 3 ingredients listed, type menus, where you’re left guessing how these are all going to come together on your plate. Meanwhile frantically searching Instagram to help fill in the blanks. When did this way of writing menus become so popular and is it here to stay?

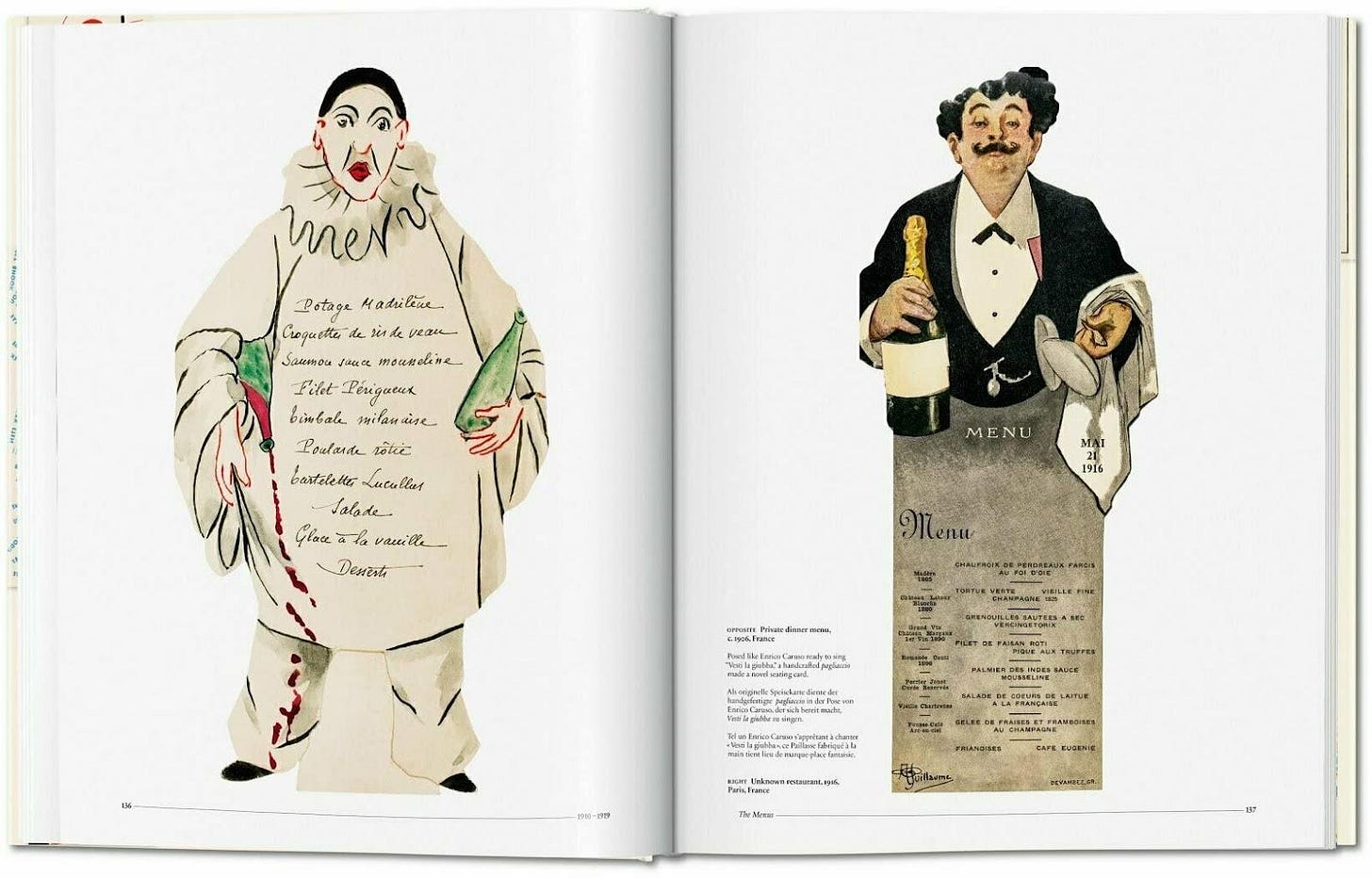

Well, let’s first take a quick jaunt down memory lane to 4000 years ago, when the first menu was carved into a stone as a gift to the ancient gods, through to the Song Dynasty and into the 18th century when menus first appeared in Europe. During this period, menus were employed by the French upper class to bring an added extravagance to their home banquets, whilst everyone else was assigned to less formal dinners in local taverns. These menus were printed on broadsheets, crammed with numerous dishes, written in cursive lettering, and encased in a decorative border. This design reflected fine dining and the spirit of aristocracy. However, at the turn of the century and after World War II, when eating out became more commonplace, creating a menu that stood out from the rest became a competitive game. Physical menus were printed with bold graphics resembling large advertisements, they mirrored art movements and even reacted to cultural events (think satirical New Yorker cartoons and pop art). Later on, menu design was squashed in favour of heavily detailed descriptions of dishes, listing methods, cuts and techniques. In the 2000s it became more favourable and advantageous to ditch the long cooking details to focus on suppliers and producers, which offered up a more ethical provenance to the dish and restaurant. Until about a decade ago when the scales tipped again, this time in favour of ultra-minimalist design and description.