Dear readers,

A little mid-week newsletter, since we missed (you) last week.

In January 2024, Marie Claire Digby, formerly of the Irish Times, asked me what the menu would look like at Ómós. I refrained from providing a conceivable sample menu because at the time, I didn’t have one. Roll on 1.5 years, and I'm still hesitant to provide you with anything of any definitive certainty. However, there have been discoveries… As we delve deeper into this project, I can confirm (as the roof of the restaurant is now almost complete and affixed to the exterior walls), I am learning more and more about who we are and what we want to be, further shaping what it is we wish to cook. Somewhere, there’s a hypothetical blackboard garnering a set of evolving thoughts and beliefs, and even flavour combinations into something that will become the Ómós menu.

1.5 years ago

The Digest has acted as a great resource for documenting these thoughts. Simply looking back at archived articles tells me what has changed in my views about food, and whether they have adapted or not in the past 4 years. For example, in that Irish Times press release, I was quoted as saying, “We will embrace an emerging Ireland and with that a developing palate. Immigration and travel over the last couple of decades have changed how we eat, and therefore, rather than being puritans of locality, we wish to cast our net further afield in search of bold flavours, focusing on ethical growing methods, building new supply chains, and finding delicious produce that makes sense seasonally. Just because it’s local doesn’t mean it’s the best option.” This sentiment still runs true, but what has changed is that I have recently learned why this is to be. I've realised that my strength as a cook is in flavour pairing, largely down to my experiences and the ingredients I’ve been exposed to. I have experienced unique ingredients on my travels - such as smoky morita and pasilla chillis in Mexico, fragrant kaffir lime leaves in Thailand, briny ferments in Denmark, and the pops of freshness attained from green coriander seeds in Spain - and learnt how to incorporate them with local ingredients so they make sense on a plate. Bringing those learnings and flavours home is exciting. The goal is to create food that tastes alive, and looks and feels vibrant, rather than foreign, disjointed, or plain weird.

When I came back to Ireland from Denmark in 2019, I returned with the presumption that I must develop a skillset derived from ancient Irish cooking techniques and ingredients; extracted from the burning embers of a fire pit or sourced from the depths of a bubbling cauldron set over the traditional Irish hearth. I was infatuated with discovering the secret larder within Irish cuisine, a mystical book preserved somewhere deep within the boglands, unearthing an encyclopedic volume of secret recipes that would make Irish food unique… I realise I was suffering of ‘Irish abroad syndrome.’ And a couple of years home, now makes me feel differently. Not because the cooking on this Island can’t be unique, but because I’m no longer interested in flying the Irish flag in that way. I feel those culinary aspirations don’t matter to me in the same way as they once did. Our traditions and heritage are still hugely dear to me, but I wish to honour them in more subtle ways, rather than to define ourselves as a restaurant that cooks Irish food. What’s most important to me is that I cook delicious food that excites me. Food I would want to eat. Cooking that makes sense to me. You’ll hopefully dine at Ómos to try delicious and exciting produce-forward cookery and experience warm hospitality. Any time I deviate from that, chuck a bucket of water over me.

There are both benefits and negatives that have come from working at noma and Geranium. Both restaurants cook with great complexity, that is, process-driven and dependent on a large staff force. We cooked with endless scope and very few limitations. Every dish was a sculptural masterpiece and a taste sensation. Training yourself out of that mindset takes time. You almost need to retrain yourself to learn that not all dishes need 10+ processes, and the best dishes are often the simplest. I recall the Restaurant Manager at noma once telling me that it would be impossible for noma to return to how they once cooked - when the cooking looked more like plates of food. The expectation was now too high. But that’s noma (maybe). Not every restaurant is noma and not every hospitality project is centred around a single meal (not least Ómós).

At Bastible, I had to quickly deviate from this mindset. I went from working in a kitchen with 50+ chefs to 5. It became about being resourceful while still executing food and practices at the high standard of work I’d learnt abroad. All this within the parameters of a small kitchen, a tight team, high covers, and small budgets. Although I sometimes felt restricted, this also sparked creativity and perhaps began to unearth a style that was more minimalistic and creative by default. When I look at restaurants and try to articulate what I admire in food, it's simplicity, paired with vibrancy, attitude, and a sense of life and providence. Noma is in its own league in my opinion. They handle food in a way that cannot be compared to anywhere else. However, often in other restaurants, when food is overworked, reshaped or overprocessed, I feel it loses a piece of its energy, and maybe its connection with where it was sourced from. As we all know, social media has made food monotonous - and menus too. There’s a huge amount of cooking and so many menus out there that feel formulaic. Tuile moulds, endless tart cases, and perfectly straight, grilled and lacquered lobster tails: we see these pop up on our feeds time and time again. But what doesn’t pop up is flavour. Flavour is something that needs to be tasted (duh) and experienced.

6 months ago

I took this upcoming excerpt from Behind the Menu - a piece I wrote last year about my food and my cooking. I had just completed a pop-up at Spry in Edinburgh, and felt quite reflective... “My approach to cooking reflects several touchpoints. My food is aromatic and complex. I am ingredient-driven and get excited by flavour. I love stories and adapting and reinterpreting dishes from other cultures to make them relevant to ours. I am inspired by highly visual food. Texture and process are important to me, while viability and sustainability should always be the defining factors of whether a dish is menu-worthy or not. I avoid plating styles designed to demonstrate my skills or seek to embellish or impress, however I am naturally drawn to finding obscure or artful ways of presenting something. Does a slice of cured fish need to be flat or is it more interesting rolled or curled? How does that alter the eating experience and how can that be done in the most natural way possible, so that it doesn’t look over-manicured (forgive the pun)? If dishes succeed in making you appreciate them momentarily, like you would in a gallery, then that's a success. If they are unsustainable in their production, causing an imbalance in the workplace, well then that's a failure. Overall, what inspires me is not just the dish but the harmony and interconnection of dishes in a menu. How wines interact with a menu takes things one step further again. With this dinner, it’s undeniably what I thought most about. At a concert, fans don’t judge an artist on one song but on their entire performance. A well-curated menu could be considered a performance. Should it be well executed and matched with great service, your guests will become your restaurant's greatest fans.” - What do you make of that?

Now:

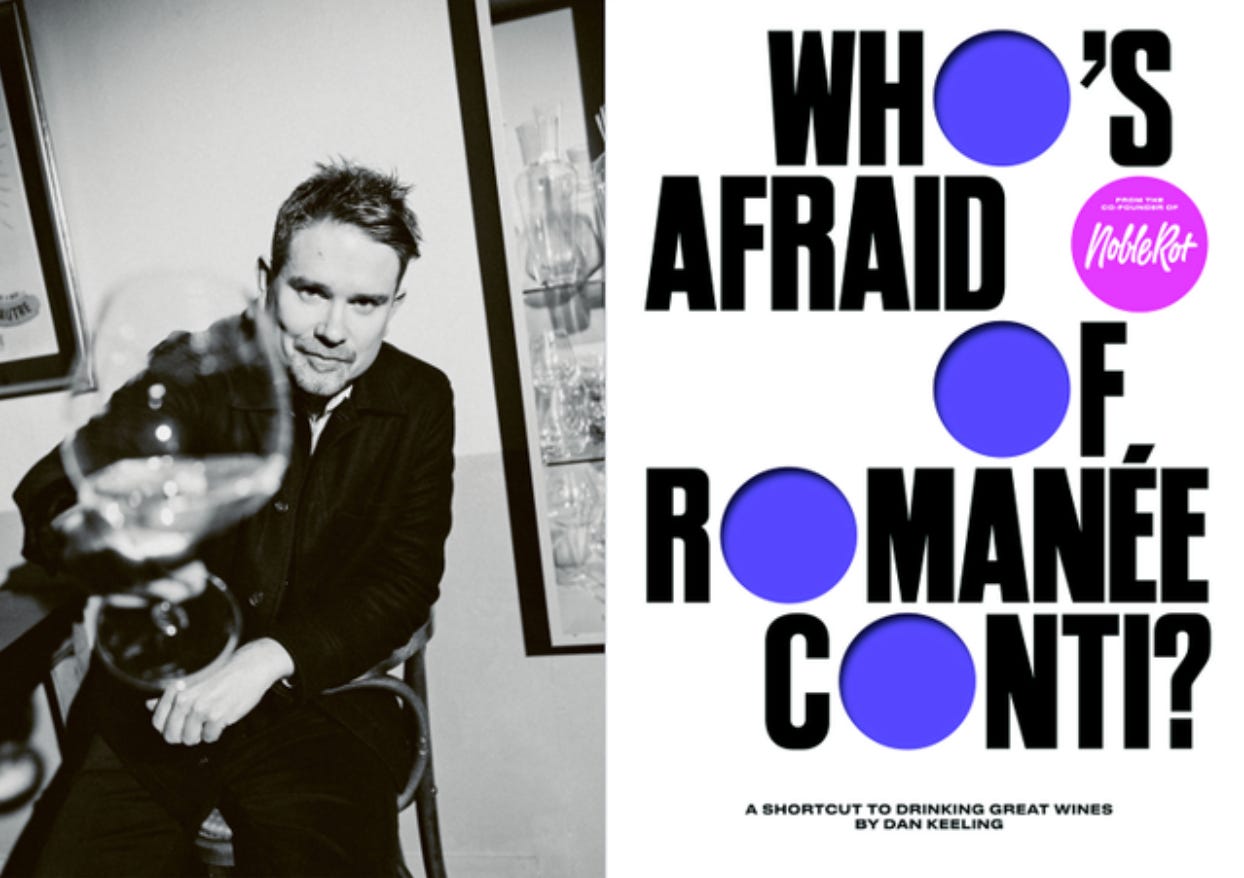

There’s no better feeling to me now than when I discover something that inspires me, whether that is something I have read or seen or tasted. I become somewhat obsessed with the place, the book or the cook, and learn everything I can about it or them. For example, I’m currently reading Dan Keeling’s Who’s Afraid of Romanée-Conti? and have become completely absorbed. I’m infatuated by his writing. He has made reading about wine accessible, cool and bloody interesting!

Recently, however, some of the best eating I have done was in Rome. I’ve admired this cook online called Mirko Pelosi for a while. He’s worked in some great restaurants (Timberyard, Sillon, Ernst and maaemo), and looked to be cooking really interesting, produce-forward dishes that I can only describe as vibrant, explorative and alive. And he’s cooking it out of a tiny wine bar called Enoteca L’Antidoto in Rome. Of course, in so many instances when you get overly hyped about a meal online, then go experience it, it's a letdown. But in this instance, the food was inspiring. Cooking practically on his own (helped by his gallant Kitchen Porter), it was his flavour combinations that were impressive and thought-provoking. Perhaps a virtue of his travels. Although I don’t want every meal to be an educational journey, I did feel like I was learning while eating Mirko’s food, and as a chef, that excites me. The hospitality was never forced, it was a wine bar after all, but the food did the talking, causing you to scoot forward, tucking into your seat, and paying closer attention to what was happening inside the dish before you.

Flavours from Enoteca L’Antidoto:

Mussels + fig leaves + red curry (with a paste using local ingredients)

9 day dry-aged Albacore tuna + Monk’s Beard dressed in sesame oil + young onions

Fennel sorbet + smoked poached strawberries + rose and dried fennel

This menu was definitely on the more experimental side, and when I asked Mirko if guests were ever on the fence or complaining about wanting something more conventional (picturing an older disgruntled Italian in search of bucatini all'amatriciana), Mirko said that all the customers come with open minds and seem to enjoy the food. This came as a relief. I've never been one to worry too much about what others think about my food, but as we edge closer to opening our own place, I find myself increasingly aware of how people will react to my cooking. What is key to remember is that as long as I am cooking a menu that I and the team would want to eat, then we’re doing the right thing.

With reference to the restaurant menu. We will be happy if you serve the turbot we ate with you at Breac House.

Love the Digest!

Graham